Blogs

AI4Science Blog

Background

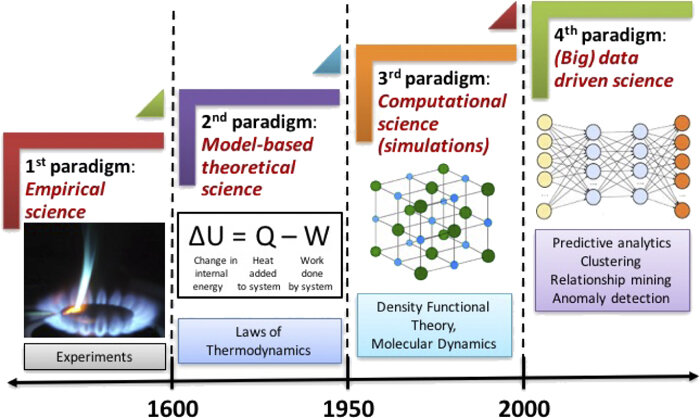

Scientific discovery has progressed through significant advancements, driven by the desire to understand the natural world. Early efforts, such as Newton’s study of motion and gravity, relied on careful observation and reasoning to discover fundamental principles.

As science advanced, theoretical models like the laws of thermodynamics were developed to explain complex phenomena and predict natural behaviors, emphasizing universal principles expressed through mathematical formulas, models, and algorithms. It seeks to formalize knowledge and derive conclusions through deductive reasoning.. These models marked a shift from observation to deeper analysis.

With growing challenges like the increasing complexity of different systems, where everything is linked. For example, ecosystems depend on interactions between animals, plants, climate, and human activity, requiring the measurement and modeling of countless variables, new methods like computational methods became essential. They allowed scientists to simulate complex systems, such as molecular interactions and ecosystems, where many variables interact in complicated ways.

While modern scientific discoveries becoming even more complicated and data-based, such as those questions involving abstract and hidden phenomena like dark matter, astrophysics, and protein foldings, the rise of integration of artificial intelligence(AI) in big data-driven science, a data-intensive calculation based-on data, combining experiment, theory and computer simulation, marked a transformative shift from traditional scientific progress that is guided by hypothesis-driven experimentation and theoretical development, and this enabled researchers to begin analyzing massive datasets using AI to recognize patterns and perform simulations and predictions in numbers of scientific fields like biology, earth science, physics math and chemistry. For instance, climate and environment science benefits from AI’s ability to model complex systems, predict environmental changes, and assess human impacts. Similarly, tools like AlphaFold and bioimaging have transformed protein folding research, advancing drug discovery and molecular biology.

In 2009, the book The Fourth Paradigm: Data-Intensive Scientific Discovery published by Tom Hey(Hey et al. 2009) identified and categorized scientific discoveries and processes into 4 basic paradigms (experimental science, theoretical science, computational science, and data-intensive science, also indicated in Figure 1). Researchers from different institutions all over the world are now trying to push the boundaries of the 4th paradigm to use AI to accelerate simulations of fundamental equations of nature, which complements and amplifies the 1st to 4th paradigms.

Preliminary Analysis

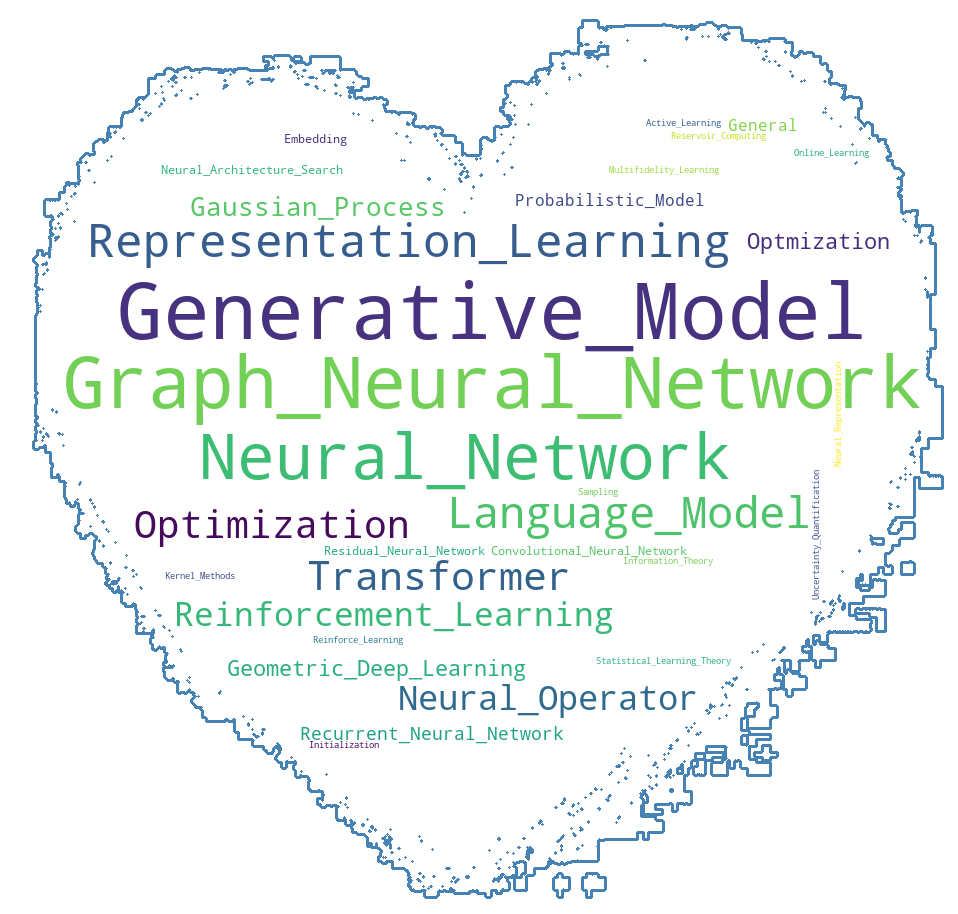

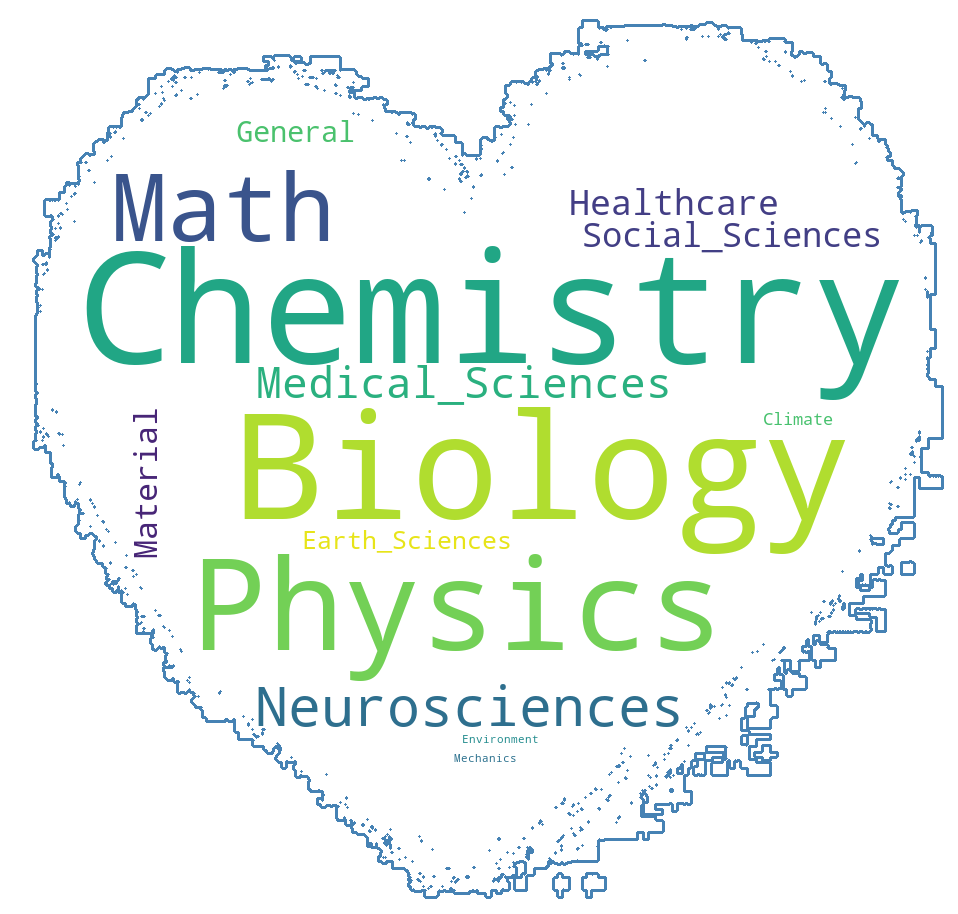

Key AI techniques discussed in AI4Science papers include “Graph Neural Networks,” “Generative Models,” “Neural Networks,” and “Reinforcement Learning.” These methods have been applied across a diverse array of fields, such as “Chemistry,” “Biology,” “Physics,” and “Neuroscience.” The visualization underscores AI’s multidisciplinary nature, extending to areas like “Medical Sciences” and “Healthcare,” highlighting its growing role in addressing complex, data-driven challenges.

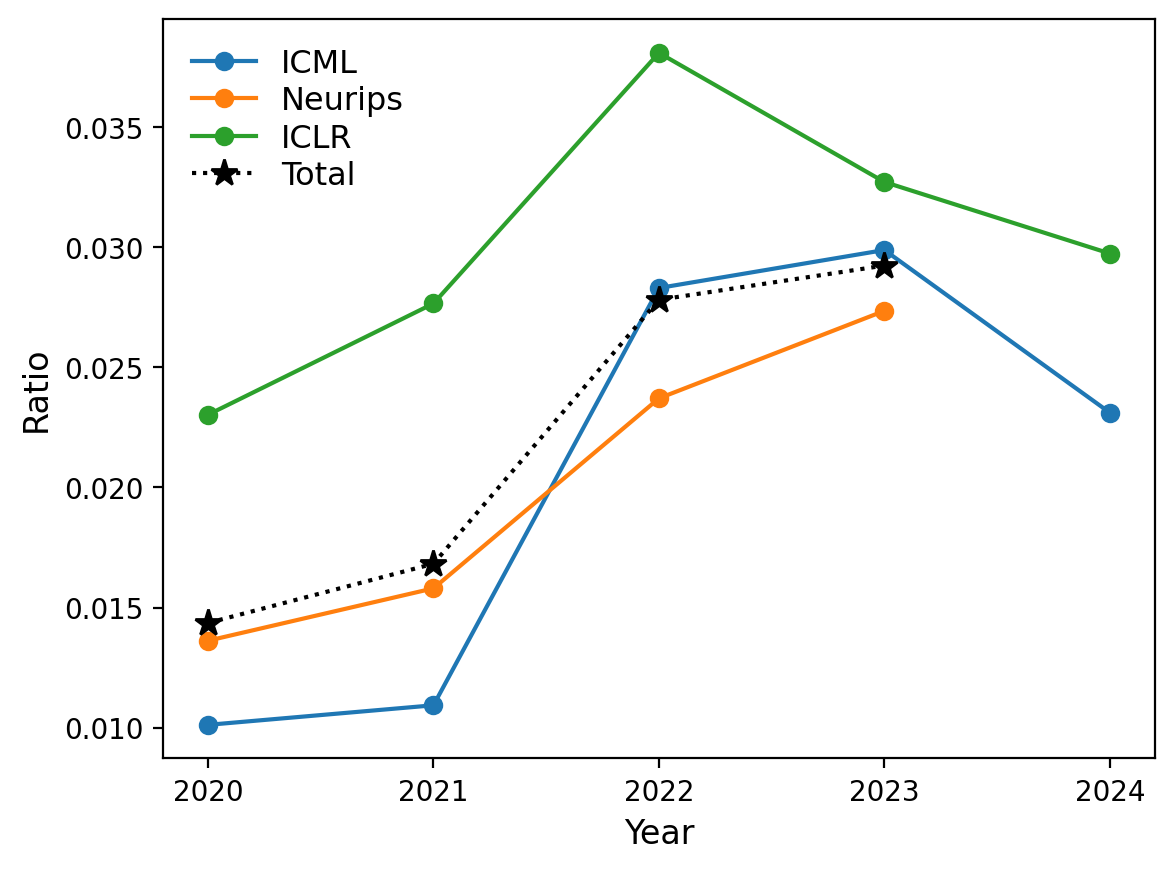

The percentage of AI4Science papers in papers from the three AI conferences shows a steady and linear increase each year. Innovation adoption typically follows a logistic s-curve model. As indicated by Figure 3, the increase in percentage from 2020 to 2021 is relatively smaller compared to the later time intervals, marking the beginning of adopting AI4Science papers, followed by steady growth in 2021 to 2022 and 2022 to 2023. We expect that the percentage of AI4Science papers will continue to growth and finally be saturated with a certain percentage in the future.

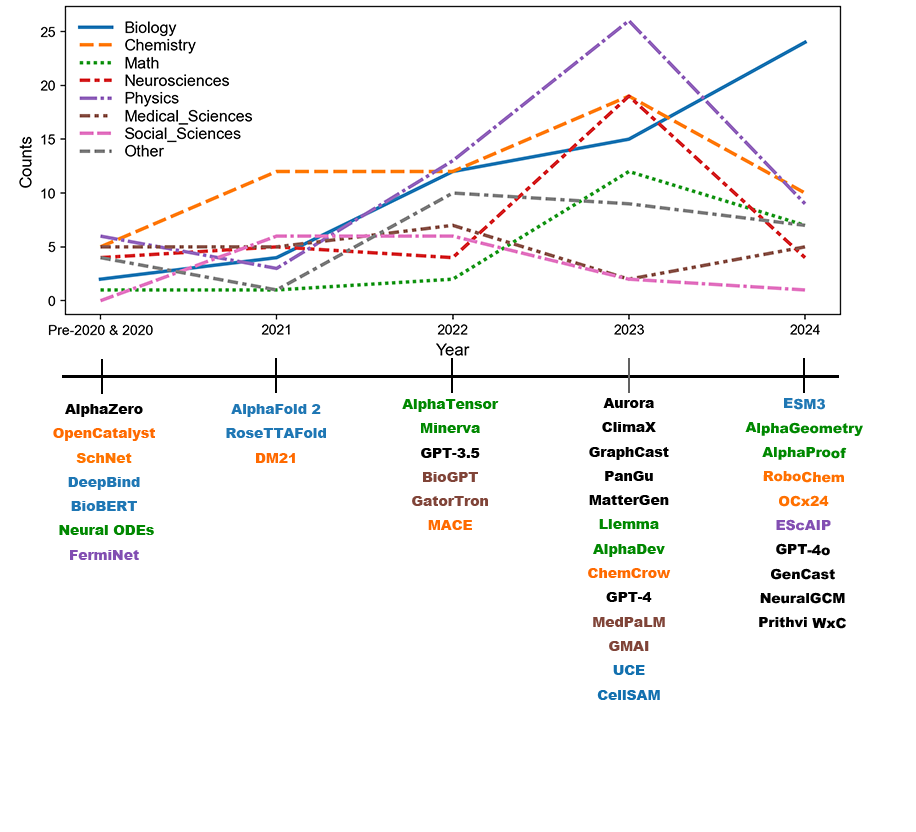

This timeline illustrates trends in research papers related to fields like biology, chemistry, math, neurosciences, physics, medical sciences, and social sciences from 2020 to 2024. Notable AI models and studies for fields like biology(Jumper et al. 2021; Baek et al. 2021; Alipanahi et al. 2015; Lee et al. 2020; Rosen et al. 2023; Moor et al. 2023; Hayes et al. 2024), chemistry(Kirkpatrick et al. 2021; Batatia et al. 2022; M. Bran et al. 2024; Chanussot et al. 2010; Schütt et al. 2017; Slattery et al. 2024; Abed et al. 2024), math(Chen et al. 2018; Fawzi et al. 2022; Lewkowycz et al. 2022; Azerbayev et al. 2023; Mankowitz et al. 2023; Trinh et al. 2024), medical sciences(Luo et al. 2022; Yang et al. 2022; Singhal et al. 2023; Moor et al. 2023), social sciences, material(Zeni et al. 2023), physics(Pfau et al. 2020; Qu and Krishnapriyan 2024),climate(Bi et al. 2023; Bodnar et al. 2024; Lam et al. 2022; Nguyen et al. 2023; Price et al. 2023; Kochkov et al. 2024; Schmude et al. 2024) and other(Silver et al. 2017)are marked along the timeline, showing how these innovations align with field-specific growth.

Fields Description & Analysis:

Biology: Major breakthroughs such as AlphaFold 2 and RoseTTAFold in 2021 transformed protein structure prediction, enabling significant advancements in drug design and molecular biology. Foundation models like Universal Cell Embeddings (UCE)(Rosen et al. 2023) released in 2023 further expanded biological research by analyzing gene expression and cellular functions. By 2024, Biology leads in AI4Science research with over 25 published papers.

Chemistry: Chemistry saw a notable rise in research paper output from 2020 to 2023, peaking around 2022. Key models like DeepMind 21 in 2021(Kirkpatrick et al. 2021) addressed limitations in Density Functional Theory (DFT), accelerating progress in material science, reaction prediction, and drug discovery. In the field of retrosynthesis, Marwin Segler’s work(Segler, Preuss, and Waller 2018) in 2018 marked a major breakthrough by combining deep learning with symbolic reasoning. This approach has enabled accurate predictions of chemical transformations and efficient synthesis pathway design. Autonomous systems like RoboChem(Slattery et al. 2024) in 2024 showcased AI’s ability to automate chemical synthesis, significantly reducing the time needed for experimentation.

Math: Research in Math remains stable with relatively low output despite its growth in 2023. Research in Math remains stable with relatively low output. Reinforcement learning (RL), has greatly impacted mathematics, enabling advancements in theorem proving, symbolic computation, and dynamic systems. RL models like AlphaProof (2024) and AlphaGeometry (2024) applied AI to complex mathematical challenges, such as theorem proving and geometric problem-solving, which have achieved a silver medal standard in the 2024 International Mathematical Olympiad (IMO).

Physics: Physics research has also been popular throughout the years, often involving applications such as fluid dynamics and quantum mechanics. AI tools played a crucial role in solving partial differential equations (PDEs) to mathematically describe the behavior of continuous systems like fluids, elastic solids, temperature distributions, electromagnetic fields, and quantum mechanical probabilities. Despite the significance of AI for PDEs, other significant fields include astrophysics, such as the imaging of the M87 black hole by the Event Horizon Telescope, and high energy physics, where AI addresses the challenges brought by massive data generated at particle accelerator facilities.

Medical Sciences: A field that is highly relevant to biology and chemistry, despite lower adoption compared to fields like biology and chemistry. Key innovations such as AI-driven bioimaging and medical language models like BioGPT(Luo et al. 2022) and Gatortron (Yang et al. 2022) have improved efficiency in disease diagnosis and treatment planning, and patient triage by analyzing medical records, symptoms, and test results. Industry leaders like NVIDIA and IBM are advancing AI advancements in healthcare.

Social Sciences: Interest peaked in 2020 and 2021 but declined thereafter, with attention shifting to more data-intensive disciplines. Popular applications include data analysis and pattern recognition, where AI algorithms process large datasets to uncover trends and correlations that inform social theories.

Neurosciences: This is also a popular field, since it is highly integrated to AI very long time. Applications typically focusing on brain activity, behaviors and brain data. One popular application is using AI to reconstruct visual experiences from human brain waves. By interpreting brain activity data as “texts” in latent space, generative models like latent diffusion models can produce realistic images conditioned on brain activity without requiring complex neural networks.

Earth Sciences: This field seems to be unpopular; however, this field actually tends to be a data-based application rather than a theory-based study. In terms of climate, major institutions and companies such as Google DeepMind, Microsoft, and Huawei invest to develop AI-driven (specifically AI for PDE) industry solutions, such as Aurora(Bodnar et al. 2024), ClimaX(Nguyen et al. 2023), GraphCast(Lam et al. 2022) and PanGu(Bi et al. 2023). From general weather forecasting to specific fields such as hydrology, and sub-seasonal climate prediction, we see great advances in this field.

Other: We note that there are still many other interesting developments in other areas, such as engineering, and materials, but they are somehow less noticeable in the AI4Science industry.

The varying research paper outputs across fields in AI4Science can reflect the properties and the nature of fields. This can be attributed to major factors such as data availability, the foundational state of the field, the nature of the discipline, and the historical evolution of fields.

One of the critical factors is data availability. Fields that tend to be more experimental typically have abundant and accessible data, which tend to see more AI-driven breakthroughs. AI works well with large datasets, where it can leverage its strengths in pattern recognition and predictive modeling. For instance, biology has benefited significantly from the availability of massive datasets, such as protein sequences and genomic information. In contrast, fields that tend to be more theory based like mathematics or social sciences often lack the kind of large, structured datasets required for data-driven AI methods, limiting the potential for rapid advancements. We have tens of thousands of protein structures, but we don’t have tens of thousands of mathematical theorems.

Similarly, in fields like climate science and high-energy physics, the high cost and infrastructure requirements for data collection make progress accessible only to a few large institutions, thereby restricting overall research output.

The foundational state of the field is also noticeable. Fields with well-established theoretical frameworks provide a solid base for AI integration. For example, in physics, partial differential equation (PDE) modeling is a highly developed area, allowing AI to seamlessly contribute to applications like fluid dynamics and climate simulations. On the other hand, fields with less structured or foundational frameworks face challenges in integrating AI effectively. Social sciences, for instance, often lack universally accepted models and theories, making it harder for AI to generate useful insights.

Finally, the historical evolution of fields influences AI integration. In older fields like mathematics and classical physics, with long-established methods, problems that are solvable have already been solved by humans, leaving only increasingly complex and less tractable problems that put these fields in a hard bottleneck. For instance, the Millennium Prize Problems have been there for a very long time, and neither humans nor AI can bring up solutions. In contrast, newer fields like neuroscience and modern biology align more naturally with AI’s strengths in handling experimental and data-driven problems.

Conclusion

Our analysis highlights the strengths of AI in accelerating scientific discovery by integrating vast datasets and improving experimental design. AI has reduced barriers in traditionally complex areas such as protein folding and chemical experiments, enabling breakthroughs at unprecedented speeds. Despite these advancements, the field also faces bottlenecks, including reliance on high-quality data, uneven field adoption, and potential over-focus on popular areas like biology.

In the future, To foster a more balanced development across different fields, the AI4Science community has to actively spotlight underrepresented fields and explore their unique problems that can fit into AI-driven research. This approach will incentivize those fields, and ensure that AI4Science evolves in a sustainable and inclusive manner, avoiding over-emphasize on a few popular fields. By providing equitable opportunities, the AI4Science community can nurture a even more healthier and more innovative trend in the future.